Refugees in Delhi: Somalian migrants have left war far behind, but price of peace is their progress

WAAGACUSUB:- "I don't know where my parents are, and I don't know where my family is. I need them here with me," wept 17-year-old Abdullah Ibrahim, before a dark silence numbed him over. He stared into the grimy wall of an Arabic restaurant in South Delhi's Khirki village, where he works as an errand boy.

He opened four folds of a blue paper and called it his only possession. The "blue card" is an identification issued by the United Nations' High Commissioner for Refugees, but in the eyes of the Indian State, it has no legal validity.

In 2016, Ibrahim fled Galkayo, a district in Somalia's north-central Mudug region. Clashes between rival militias Galmudug and Puntland in central Galkayo city had killed at least 29 and wounded more than 50. The district is under the divided control of the warring militias, and last year, when conflict erupted over buildings planned in the region, schools were forced to shut and civilians fled for their lives.

Amnesty International, a non-governmental organisation that focusses on human rights, confirmed in its 2016/2017 report that armed conflict continues between Somali Federal Government (SFG) forces, African Union Mission in Somalia (AMISOM) peacekeepers and al-Shabaab, a jihadist fundamentalist group that has a history of killing civilians in public by firing mortars, beheading and stoning, and carrying out amputations and floggings.

The report details that more than 50,000 civilians were killed, injured or displaced as a result of the armed conflict and generalised violence, while about 4.7 million people needed humanitarian assistance; 950,000 didn't have food security.

He opened four folds of a blue paper and called it his only possession. The "blue card" is an identification issued by the United Nations' High Commissioner for Refugees, but in the eyes of the Indian State, it has no legal validity.

In 2016, Ibrahim fled Galkayo, a district in Somalia's north-central Mudug region. Clashes between rival militias Galmudug and Puntland in central Galkayo city had killed at least 29 and wounded more than 50. The district is under the divided control of the warring militias, and last year, when conflict erupted over buildings planned in the region, schools were forced to shut and civilians fled for their lives.

Amnesty International, a non-governmental organisation that focusses on human rights, confirmed in its 2016/2017 report that armed conflict continues between Somali Federal Government (SFG) forces, African Union Mission in Somalia (AMISOM) peacekeepers and al-Shabaab, a jihadist fundamentalist group that has a history of killing civilians in public by firing mortars, beheading and stoning, and carrying out amputations and floggings.

The report details that more than 50,000 civilians were killed, injured or displaced as a result of the armed conflict and generalised violence, while about 4.7 million people needed humanitarian assistance; 950,000 didn't have food security.

As per the report, the federal Parliament passed a law in January to protect and rehabilitate IDPs and Somali refugees, but its implementation was slow. Over 1.1 million Somali refugees remained in neighbouring countries and the wider diaspora. As violence intensified in Yemen, Somalis who had fled continued to return home. By the end of the year, over 30,500 Somalis were back.

Meanwhile, other host countries, including Denmark and the Netherlands, intensified pressure on asylum-seekers and refugees to return to Somalia, saying security had improved in their country. As of end December 2014, there were some 31,000 refugees and asylum-seekers registered with UNHCR in India. Out of this, 654 were from Somalia.

Ahmad Usman Ali says he came to India last year from Bosaso, a city in Somalia's northeastern Bari province. "I am coming to India to study something, to increase my knowledge. I don't have someone connecting me to what I want, I don't have any help," he said, adding that many Somali refugees study English and computer courses at UN's Bosco centre in Malaviya Nagar in South Delhi, which is also where many of them live.

Bosco is part of the Don Bosco Global Network spread across 135 countries that runs educational institutions along with vocational and technical training centers, essentially for the benefit of displaced youth.

Ali holds his palms over his ears and then pulls them away, saying he doesn't hear the cacophony of bombs and bullet shells clashing into tins. "There is peace, we are at peace here, but we are not going to progress," he remarked.

Adil Hasan, born to a Somali mother, grew up in Yemen. By September 2014, 334,512 people across Yemen were officially registered as "internally displaced" due to fighting. He told Firstpost that he moved to Somalia in 2015 and that's when he saw his grandmother die before his eyes. It was then that his family set out for Indian shores. "A broker brought us here. We have peace but my family does nothing. But we have a chance to survive here," he said, sharing a story that is both intensely personal and yet universal among refugees.

Abdiqani, who is a community leader of the Somalis and appeals to the United Nations on their behalf, told us that most of his countrymen live in Hyderabad's Tuli Chowk and Mehdipatnam, while a third of them live in and around South Delhi's ghettos. "Arabic speaking people mostly go to Hyderabad. Refugees also live in that city because the weather is better, rents are cheaper and the food suits them. They often act as translators, and are even promised Rs 6,000 to Rs 7000 per case, but are actually paid much less," he said.

Abdiqani further added that he collects case numbers and appeals to the UN on behalf of other Somalis regarding updating of cases. He had lost his parents to violent clashes in Marka, near the old port town in the Lower Shebelle province. "Those who come here from Mogadishu, but have families who work in the government back home, come on student visas and go back once they get their degrees," he said.

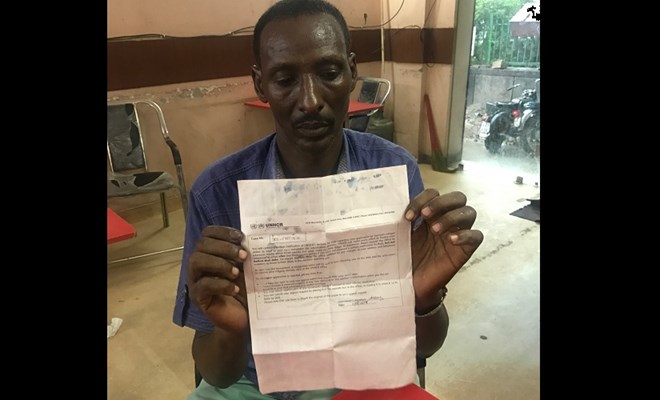

A Somali refugee claims he has spent close to a year waiting for the UNHCR to issue a blue refugee card in his name. He holds out a document that confirms his case is under consideration by the UN. Firstpost/Pallavi Rebbapragada

"But the refugees are different, they can apply only for the 'long-term visa'," Abdiqani said, alleging that the Foreign Regional Registration Office (FRRO) is often rude to refugees and asks them why they are living here. "I have recently written to the UN about 17 cases where they don't even have a blue card; these include families and individuals. As an advocate, I can tell you that the fear of being deported is real," he said.

Another problem the community faces in India is racial discrimination. "People confuse us with Nigerians and think we're here to drink and break the laws, but we are different. Our colour also makes it harder for us to get houses on rent," said Ali, who came here from Mogadishu in 2009.

Within the confines of the handful of Bosco centres in New Delhi, Somali girls wrap "garees" (a dress that resembles a saree) around them and keep the flame of their culture alive by performing the Dhaanto folk dance that marks tribal festivities in the Somali Peninsula, also known as the 'Horn of Africa'.

Somali culture and the agency that humanises it, are both near invisible in India.

India has signed neither the 1951 United Nations Refugee Convention nor its 1967 Protocol. It doesn't have on its statute book a specific law to govern refugees. The care and treatment of refugees falls under India's Registration of Foreigners Act of 1939, the Foreigners Act of 1946 and the Foreigners Order of 1948. The Indian Evidence Act, the Indian Penal Code and the Code of Criminal Procedure apply to refugees who are living on Indian soil.

Meanwhile, other host countries, including Denmark and the Netherlands, intensified pressure on asylum-seekers and refugees to return to Somalia, saying security had improved in their country. As of end December 2014, there were some 31,000 refugees and asylum-seekers registered with UNHCR in India. Out of this, 654 were from Somalia.

Ahmad Usman Ali says he came to India last year from Bosaso, a city in Somalia's northeastern Bari province. "I am coming to India to study something, to increase my knowledge. I don't have someone connecting me to what I want, I don't have any help," he said, adding that many Somali refugees study English and computer courses at UN's Bosco centre in Malaviya Nagar in South Delhi, which is also where many of them live.

Bosco is part of the Don Bosco Global Network spread across 135 countries that runs educational institutions along with vocational and technical training centers, essentially for the benefit of displaced youth.

Ali holds his palms over his ears and then pulls them away, saying he doesn't hear the cacophony of bombs and bullet shells clashing into tins. "There is peace, we are at peace here, but we are not going to progress," he remarked.

Adil Hasan, born to a Somali mother, grew up in Yemen. By September 2014, 334,512 people across Yemen were officially registered as "internally displaced" due to fighting. He told Firstpost that he moved to Somalia in 2015 and that's when he saw his grandmother die before his eyes. It was then that his family set out for Indian shores. "A broker brought us here. We have peace but my family does nothing. But we have a chance to survive here," he said, sharing a story that is both intensely personal and yet universal among refugees.

Abdiqani, who is a community leader of the Somalis and appeals to the United Nations on their behalf, told us that most of his countrymen live in Hyderabad's Tuli Chowk and Mehdipatnam, while a third of them live in and around South Delhi's ghettos. "Arabic speaking people mostly go to Hyderabad. Refugees also live in that city because the weather is better, rents are cheaper and the food suits them. They often act as translators, and are even promised Rs 6,000 to Rs 7000 per case, but are actually paid much less," he said.

Abdiqani further added that he collects case numbers and appeals to the UN on behalf of other Somalis regarding updating of cases. He had lost his parents to violent clashes in Marka, near the old port town in the Lower Shebelle province. "Those who come here from Mogadishu, but have families who work in the government back home, come on student visas and go back once they get their degrees," he said.

A Somali refugee claims he has spent close to a year waiting for the UNHCR to issue a blue refugee card in his name. He holds out a document that confirms his case is under consideration by the UN. Firstpost/Pallavi Rebbapragada

"But the refugees are different, they can apply only for the 'long-term visa'," Abdiqani said, alleging that the Foreign Regional Registration Office (FRRO) is often rude to refugees and asks them why they are living here. "I have recently written to the UN about 17 cases where they don't even have a blue card; these include families and individuals. As an advocate, I can tell you that the fear of being deported is real," he said.

Another problem the community faces in India is racial discrimination. "People confuse us with Nigerians and think we're here to drink and break the laws, but we are different. Our colour also makes it harder for us to get houses on rent," said Ali, who came here from Mogadishu in 2009.

Within the confines of the handful of Bosco centres in New Delhi, Somali girls wrap "garees" (a dress that resembles a saree) around them and keep the flame of their culture alive by performing the Dhaanto folk dance that marks tribal festivities in the Somali Peninsula, also known as the 'Horn of Africa'.

Somali culture and the agency that humanises it, are both near invisible in India.

India has signed neither the 1951 United Nations Refugee Convention nor its 1967 Protocol. It doesn't have on its statute book a specific law to govern refugees. The care and treatment of refugees falls under India's Registration of Foreigners Act of 1939, the Foreigners Act of 1946 and the Foreigners Order of 1948. The Indian Evidence Act, the Indian Penal Code and the Code of Criminal Procedure apply to refugees who are living on Indian soil.

0

0

Refugees in Delhi: Somalian migrants have left war far behind, but price of peace is their progress

WAAGACUSUB:-